(a following text by by Robert Ellsberg taken from http://www.melodice.se/manniskor/EttyHillesum.htm under the Fair Use Copyright Doctrine)

Etty Hillesum wrote in her diary: “Sometimes when I stand in some corner of the camp, my feet planted on earth, my eyes raised towards heaven, tears run down my face, tears of deep emotion and gratitude.” Does this sound like a passage from a young girl’s summer camp diary? Well, the camp she speaks of is a Nazi death camp. What Etty Hillesum stands for is gratefulness against all the odds. This makes her shine as an example for all of us, a witness to sheer enthusiasm for life. — Br. David

“God is not accountable to us, but we are to Him. I know what may lie in wait for us…. And yet I find life beautiful and meaningful.”

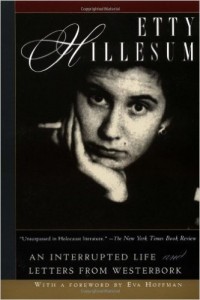

Little is known of the external life of Etty Hillesum, a young Jewish woman who lived in Amsterdam during the Nazi occupation and who died as one of the millions of victims of the Holocaust. This obscurity is in contrast with her well-documented internal life. From the day when Dutch Jews were ordered to wear a yellow star up to the day she boarded a cattle car bound for Poland, Etty consecrated herself to an ambitious task. In the face of her impending death, she endeavored to bear witness to the inviolable power of love and to reconcile her keen sensitivity to human suffering with her appreciation for the beauty and meaning of existence. For the last two years of her life Etty kept a meticulous diary, recording her daily experiences and the unfolding of her interior response. Published four decades after her death, this book was quickly recognized as one of the great moral documents of our time.

Etty maintained a clear sense of solidarity with the Jewish people. But her personal reflection was nourished by an eclectic range of sources, including Rilke, the Bible, St. Augustine, and Dostoevsky. When a friend exclaimed indignantly that her attitude on the love of enemies sounded like Christianity, she responded, “Yes, Christianity, why ever not?” But in fact she had little interest in organized religion of any kind. In a time when everything was being swept away, when “the whole world is becoming a giant concentration camp,” she felt one must hold fast to what endures – the encounter with God at the depths of one’s own soul and in other people.

There is an earthy and embodied dimension to Etty Hillesum’s spirituality. She described her romantic adventures with no more reticence than she reserved for descriptions of her prayer. For Etty, everything – the physical and the spiritual without distinction – was related to her passionate openness to life, which was ultimately openness to God.

They are out to destroy us completely, we must accept that and go on from there…. Very well then … I accept it…. I work and continue to live with the same conviction and I find life meaningful….

In the meantime her life was unfolding within the tightening noose of German occupation. Etty’s effervescence might seem to resemble a type of manic denial. The fact is, however, that she seems to have discerned the logic of events with uncommon objectivity. In this light, her determination to affirm the goodness and beauty of existence becomes nothing short of miraculous. Her entry for July 3, 1942, reads:

“I must admit a new insight in my life and find a place for it: what is at stake is our impending destruction and annihilation…. They are out to destroy us completely, we must accept that and go on from there…. Very well then … I accept it…. I work and continue to live with the same conviction and I find life meaningful…. 1 wish I could live for a long time so that one day I may know how to explain it, and if I am not granted that wish, well, then somebody else will perhaps do it, carry on from where my life has been cut short. And that is why I must try to live a good and faithful life to my last breath; so that those who come after me do not have to start all over again.”

For Etty, this affirmation of the value and meaning of life in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary became her guiding principle. In the midst of suffering and injustice, she believed, the effort to preserve in one’s heart a spirit of love and forgiveness was the greatest task that any person could perform. This, she felt, was her vocation.

With increasing regularity, Etty described her compulsion to drop to her knees in prayer. Toward the end of her journals, God had become the explicit partner of her internal dialogue:

God take me by Your hand, I shall follow You faithfully, and not resist too much, I shall evade none of the tempests life has in store for me, I shall try to face it all as best I can…. I shall try to spread some of my warmth, of my genuine love for others, wherever I go…. I sometimes imagine that I long for the seclusion of a nunnery. But I know that I must seek You amongst people, out in the world. And that is what I shall do…. I vow to live my life out there to the full.

Etty worked for a while as a typist for the Jewish Council, a job that delayed her deportation to the transit camp at Westbork. Eventually she renounced this privilege and volunteered to accompany her fellow Jews to the camp. She did not wish to be spared the suffering of the masses. In fact, she felt a deep calling to be present at the heart of the suffering, to become “the thinking heart of the concentration camp.”

Her sense of a call to solidarity with those who suffer became the specific form of her religious vocation. But it was not a vocation to suffering as such. It was a vocation to redeem the suffering of humanity from within, by safeguarding “that little piece of You, God, in ourselves.”

I know that a new and kinder day will come. I would so much like to live on, if only to express all the love I carry within me. And there is only one way of preparing the new age, by living it even now in our hearts.

On September 7, 1943, Etty and her family were placed on a transport train to Poland. From a window of the train she tossed out a card that read, “We have left the camp singing.”

She died in Auschwitz on November 30. She was twenty-nine.